Headlines in recent weeks have been dominated by labour shortages faced by certain industries. Business leaders have called for the government to loosen migration rules to help ease the crisis. However the Prime Minister largely refused and accused industry of being “addicted to cheap foreign labour.” So is the labour market crisis a result of Brexit, Covid-19 or something else entirely?

In his Conservative Party Conference Speech Mr Johnson stated, “We are not going back to the same old broken model with low wages, low growth, low skills and low productivity, all of it enabled and assisted by uncontrolled immigration.”

His ambition is for the UK to become a high skilled, high wage economy. How quickly the transformation can take place remains to be seen? The Prime Minister almost make it sound as if he’s spotted there are more unemployed people in the country than there are advertised vacancies and assumes matching the candidate to an available role is simple. Yet, how quickly the transformation can take place remains to be seen? In meantime doubts exist as to whether there are enough skilled workers to fill the specialist job vacancies.

Despite his feuds with various leaders of commerce the good news for Boris is that the labour crisis is a consequence of demand returning to the economy post pandemic. The latest figures released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) demonstrate several positive trends.

Key Employment Statistics

- Payroll employees increased by 207,000 in September to a record 29.2 million in September 2021 returning to pre-pandemic levels.

- Job vacancies in July to September 2021 were at a record high of 1,102,000, an increase of 318,000 from pre-pandemic (January to March 2020) levels

- Average Regular Earnings (excluding bonuses) growth rate is estimated at between 3.2% and 4.4% by the ONS for July.

- Employment rate (all aged 16 to 64) in September up 0.5% to 75.3% though still 1.3% below February 2020

- Unemployment rate (all aged 16+) down 0.4% though this is still 0.5% higher than February 2020 with approximately 150k more people out of work

Is the Labour Market Crisis Because EU Workers Have Left the Country?

There has been much speculation that, an exodus of EU nationals following the removal of the freedom of movement in January 2020 along with people returning home to be with loved ones throughout the C-19 crisis, are clear reasons why many employers are currently experiencing difficulty in finding suitable recruits for their vacancies.

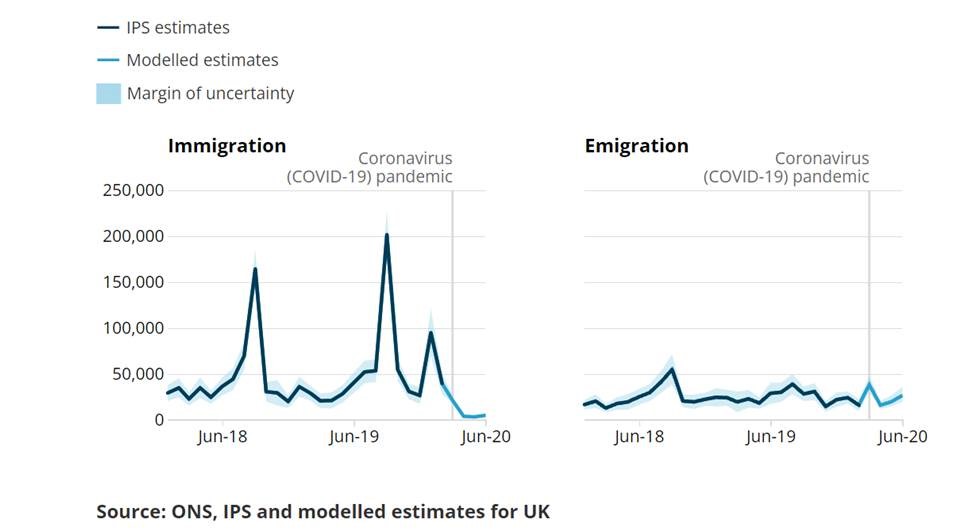

As the impact of Covid-19 pandemic eases more information will be compiled and greater analysis will of course take place. Though data released by the ONS so far appears to indicate that it’s not been the volume of people that left the UK immediately after the terms of Brexit were agreed that has contributed significantly to our current labour market issues. Emigration up to the middle of 2020 didn’t spike higher than in proceeding years. In fact it was far higher in late 2018 as EU workers perhaps hedged their bets on the outcome of the Brexit negotiations, that were still on going at that stage?

The ONS clarifies that their figures at this stage are best estimates as their usual source for measuring migration, the International Passenger Survey (IPS), was suspended at the start of the pandemic. Instead, they are using experimental statistical models. Though from our interpretation of their figures, the problem currently facing the UK labour market is potentially more a consequence of the roughly 300k people that would have been expected to come to these shores between September 2019 and Dec 2020. There appears to be a correlating drop off in migration to the UK from the point approaching when EU visa requirements came into force. Shortly after which the pandemic obviously kicked in as well.

Where Will We Find Workers?

New recruits have certainly been needed in certain sectors as the economy has reopened. Yet there remains 1.5 million unemployed people in the U.K. That’s 150k more than when the effects of the pandemic kicked in. Though they might not have the required skills to plug the gaps right now it does makes sense to invest in them, so that hopefully they can do so in the future.

Deputy Prime Minister Dominic Raab is also leading a campaign that promotes the benefit of employing newly released prisoners. 45,000 face difficulties each year as they re-enter the jobs market. He has been keen to highlight their commitment and dedication as well as the wider societal benefits.

However that doesn’t really solve the current crisis. Abattoir workers and HGV drivers for example take time to acquire sufficient skill, qualifications, knowledge and experience. One solution, though again in the longer term, is that relatively early in the pandemic high levels of redundancies took place. 20,000 took place in the motor trade wholesale, retail & repair sector alone. A proportion of those workers will have a degree of financial security from their respective pay outs and may seek to retrain in the areas experiencing demand in the jobs market?

There is also the possibility that more output will be achieved from those already in positions. The ONS figures revealed that total weekly hours worked in the UK reached 1.02 billion hours in June to August 2021. This quarterly increase of around 30% coincided with coronavirus related restrictions easing. However it is still 30.9 million below pre-pandemic levels (December 2019 to February 2020). Potentially many workers who have been placed on part-time hours will be offered the opportunity to take on bigger workloads. Thus reducing the number of heads required.

The government has stepped back from its ideological position and conceded to grant short term worker visas for key pinch points that stand to affect the economy’s supply chain. Though press reports have indicated that take up by foreign nationals has been slow, perhaps due to the temporary nature of the contracts on offer.

Will the Furlough Scheme Ending Help the Jobs Market?

The end of the furlough scheme should have a beneficial impact on the resource available for recruiters. Though it is clearly not great news in the short –term for people that had come to rely on it. The near £70bn scheme at one point or another covered the wages of 11.6 million people. According to research by the Resolution Foundation almost one million workers were estimated to still be on the scheme when it closed at the end of September.

The Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) also ended on 30 September. The fifth grant opened for applicants on the July 29th and by September 15th, 1.1 million claims had been made.

International travel still had high furlough rates but the loosening of travel restrictions should help minimise job losses in that sector. And how many of those who lose their job will become unemployed? The Resolution Foundation points out that before the pandemic, only 35% of people who had been made redundant in the previous three months were still unemployed. This along with record high vacancies may explain why the Bank of England predicts only a small rise in unemployment as the scheme ends.

Is Long Covid Having An Impact?

One issue from the ONS’s latest release is that the UK economic inactivity rate was still estimated to be 0.9% higher than before the pandemic. Though the rate was 0.2 % lower than the previous quarter. A House of Commons Research Paper on the “Impact of the Labour Market” notes that inactivity is more severe amongst the extremes of younger and older eligible workers.

A person of working age is economically inactive if they are out of work and not actively looking for work. There are many potential reasons for the spike in this statistic and the high cases of long Covid impacting the UK workforce is just one suggestion. Time will tell if the economic inactivity rate will return to its previous levels and the trend appears to indicate that it will.

How Widespread is the Labour Crisis?

Analysis by leading financial services firm Citi concludes, “We should not be fooled by headlines of high-profile examples of labour shortages and supply disruptions into thinking the economy is overheating generally. In many sectors demand remains below pre-pandemic levels, the labour market is quite loose, and the outlook for wages remains rather weak.”

Their report states that there are huge imbalances in the economy at the moment. Certain sectors are experiencing constrained supply, in others “demand has grown” but “demand remains weak” in many areas.

So the headlines in the press may be painting a false picture of a booming recovery with significant wage inflation as employers scrabble to secure the few available workers. Actually many sections of the economy are not experiencing a labour shortage. However those that rely on workers with relatively long training cycles or those that had a high percentage of skilled foreign labour pre-Brexit and the pandemic, have been worst affected.